Russian Verbs

A comparative review

Preface

I’ve realized only recently: advanced foreign language material assumes a background in linguistics. It’s embarrassingly obvious now but grappling with strange Russian features with no basis for comparison feels a lot like wandering in the dark. Since having plugged through an English grammar textbook, not only have I found myself paying more attention to speaking English more effectively in conversation, several Russian concepts I’d known intuitively have re-anchored themselves around real and simple explanations — usually in a satisfying, "aha" moment.

Here, to document a bit of what I’ve learned, I’ll do a deep dive on the Russian verb, paying specific attention to what I think is typically glossed over in Russian texts. I’ll try to present the English and Russian analogs alongside each other. Although I think it would be most valuable as a backfill for Russian-learners (of any level), I’ll provide definitions and transliterations so that familiarity in neither linguistics nor Russian are prerequisite.

Inflection and The Case System

The most striking difference between English and Russian is their morphology. Where English relies on a strict word order and a cobbling-together of words called periphrasis to signal grammatical role, Russian changes the word to suit it by inflection, a type of mutation. English makes a limited use of this in affixes (e.g. plural -s, repeated re-, opposites un-, in-, de- and anti-, ability -able) and derivation (e.g. nasty, nastily, nastiness) but Russian is so liberal in word order that it’s used more for emphasis than the meaning of the words themselves.

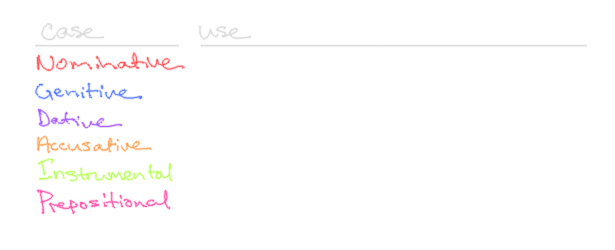

Inarguably, the most prominent example of inflection is its case system of declension. Although I limit my discussion here to the verb, this system is too pervasive to be avoided. Here’s a quick summary of the six cases it distinguishes:

-

The nominative case is the "dictionary form" of the word and is reserved for the subject (e.g. “I don’t think so”).

-

The accusative case is used to indicate the direct object (e.g. "I shook my head").

-

The genitive case is used to indicate possession and composition (e.g. "Natives’ territory", “a cup of water”)

-

The dative case is used to indicate indirect objects and other notions of recipiency or benefit (e.g. "I gave them my opinion")

-

The instrumental case is used to indicate accessory (e.g. "with friends") or means (e.g. “by the grace of God”).

- The prepositional case is used to subordinate prepositional-oblique objects (e.g. "at the end of the road").

Because only the presence of these kinds of changes are important to the discussion and not their actual mechanics, it should be enough that I key each case to a specific color:

The Core Types

Subjects and Objects

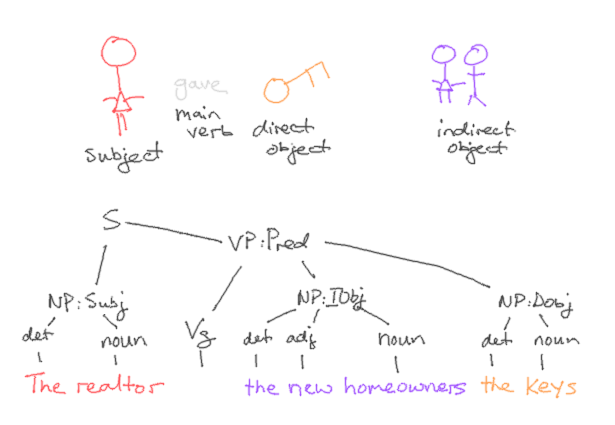

In both English and Russian, every expression ultimately centers around an action given by the main verb. Whether it’s asking or telling, sure or speculative or occurring in the past or the present, verbs in these languages can be modeled as the relationship between a cast of three:

The subject is the actor, origin or agent of the action. In English, it’s present — actually or implied — in every sentence, is always a noun phrase and frequently occurs in the sentence before the verb. Nouns that occur in the second (predicate) half of the sentence, usually after the verb, are the recipients: the direct object to the action and, if the verb itself creates a type of recipiency (e.g. to give) or benefit (e.g. to advise), the indirect object to the direct one.

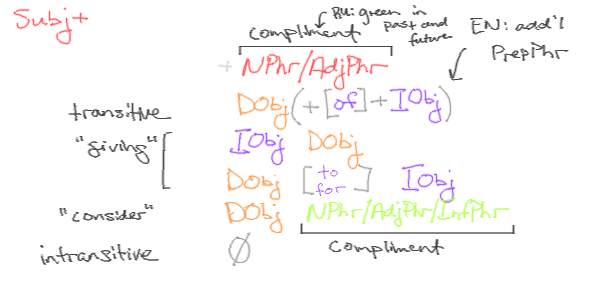

Because each English sentence can be characterized by the use of its main verb and those main verbs behave in only a finite number of ways, each sentence can be broadly but distinctly categorized into a few core types:

Transitives

Transitive verbs require direct objects. They come in three varieties:

-

Monotransitive (or VT) verbs are perhaps the most frequently-occurring and most easily-identifiable type. It accepts only the direct object (e.g. "I packed a lunch").

-

Ditransitive (or Vg or "giving") verbs accept, first, an indirect object (as a noun or prepositional phrase) and, second, a direct object (e.g. “The realtor gave the new homeowners the keys.”). It has a second form involving the prepositions for and to (e.g. “The realtor gave the keys to the new homeowners”).

- Double transitive (or Vc or attributive-ditransitive or "considering") verbs are similar in shape to Vg verbs but similar in character to (the soon-covered) linking verbs. They accept the direct object in the first slot and a complement to the object is being compared to in the second. This complement can be a noun, adjective or infinitive phrase and doesn’t complete the verb, but the object.

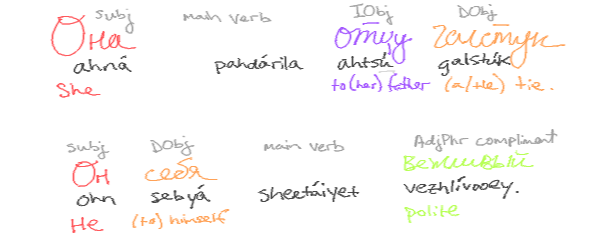

Russian, as noted above, indicates the direct and indirect object roles with the accusative and dative cases, respectively. For double transitives, Russian indicates that the object and complement have a "linking" relationship by applying the instrumental to the latter. Again, this allows words to change order without changing meaning.

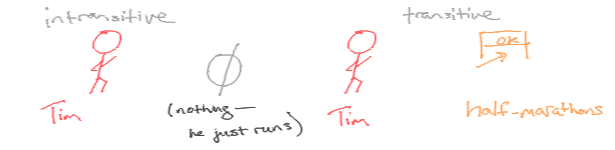

Intransitives

Intransitive verbs, oppositely, do not accept objects. There are verbs in both languages that indicate a kind of ambient doing — notably state (e.g. "I’m thinking" / “я думаю”), sensation (e.g. “His hands shook” / “его руки дрожали”) and motion (e.g. “The boat lurched” / “Лодка кренилась”). For these, it usually intuitive that an object doesn’t follow.

It's also important to note that it's the use of a verb that commits it to a type. Many verbs can assume multiple types.

Copulars

Copular (or linking) verbs are a specific flavor of intransitive. They show up in English in verbs like to become, to remain, to turn and to feel. Like double transitives, they’re completed with a complement that "links" a certain quality or identity to a noun phrase but, instead of pairing with the object (again, here absent), it pairs with the subject. Like with double transitives, Russians use the instrumental to do the “linking”. The most common Russian linking verbs line up pretty well with our own, e.g. to become (становиться), to remain (оставаться), to seem (казаться), to be considered (считаться), to assign/appoint (назначать).

To be, both an intransitive and copular verb, is perhaps the simplest, most frequently used and most irregular one in both languages. In English, it’s one of three verbs with full conjugation (i.e. am, were, is, been, are, being). The Russian to be, быть, is somewhat unique in that it lost all but one of its (present-tense) conjugated forms, есть. In both languages, it’s used as an auxiliary. In English, to be can hide as either an existential clause (there + be, e.g. "There’s a mower in the shed") or with the expletive it (e.g. “It’s nice outside”).

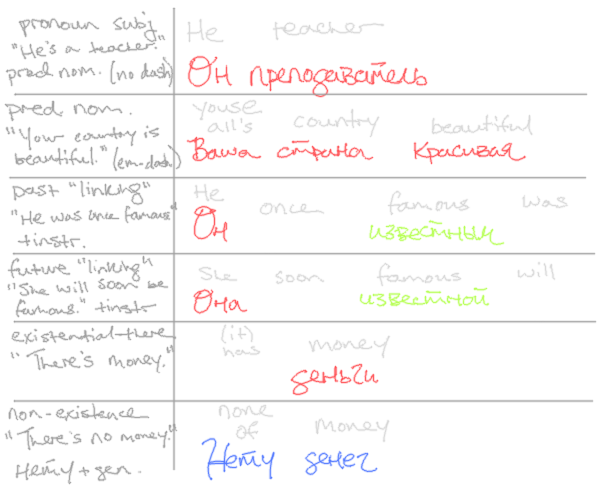

Usage of be is straightforward in English but nuanced in Russian. Typically, быть is omitted. Unless the subject is a pronoun, it’s usually delineated in writing from the predicate by an em-dash. The predicate takes the nominative in the present tense and the "linking" instrumental in the other tenses. Existential clauses, on the other hand, use the one conjugated form быть did retain: the third-person singular есть. Negation is a condition handled by the genitive, so that’s applied when negating an existential clause (e.g. нету денег, “(there is) no money”) but, confusingly, only in the present tense. For the others, a simple “not” (не) suffices.

Voicing

Reflexives and -ся

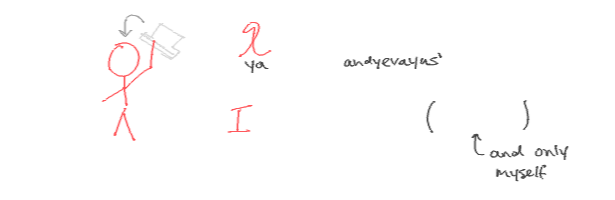

In more formal contexts, it’s common to find являться (another to be; shares a root with to appear) as a fancier, instrumental-governed is. Являться — along with the examples I gave for copulars above — belong to one of a few classes of verbs bearing the characteristic suffix -ся (sya) — а contraction for себя (sebya, [to] oneself). These are confusingly conflated in Russian textbooks as reflexive verbs.

A reflexive verb is any one in which the direct object is the same as the subject. In English, we use a set of dedicated reflexive pronouns to avoid having to repeat the subject or confuse it with another. The Russian reflexive verb is autocausative, meaning that its use alone implies себя — itself baked into the word. While there are a few true Russian reflexive verbs (e.g. мыться / to wash oneself, бриться / to shave oneself, одеться / to dress oneself), the -ся suffix can be effectively "added" to any transitive verb in the language, by that each one is paired with a distinct intransitive verb that has the suffix.

"Intransitive" is probably a better name for these words because their other uses don’t have much to do with reflection. A few of these are reciprocal action (where the object is implied to be “each other”, e.g. мы встречаемся, we’re meeting), actions denoting a habit or permanent characteristic (e.g. собака кусается, the dog bites) and an impersonal construction for weak expression (e.g. мне хотелось бы... / I kinda would like…). Even worse still, some -ся verbs aren’t paired with transitives and exist only intransitively (e.g. гордиться / to be proud of, смеяться / to laugh, надеяться / to hope) and some take on a completely different meaning between the two (e.g. находить and находиться / to find and to be located, слушать and слушаться / to listen and to obey).

The Passive Voice

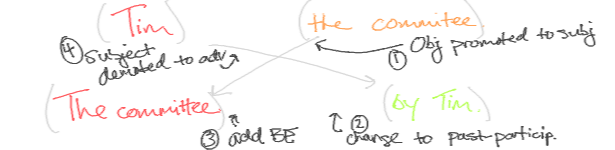

The last use of the intransitive is in the construction of the passive voice.

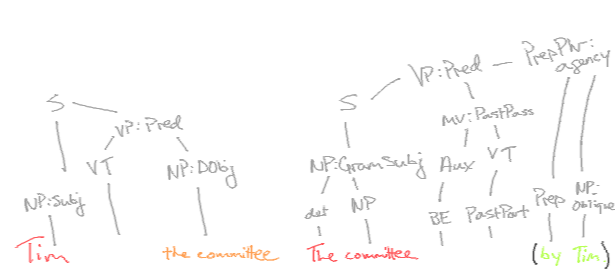

-

Remove the subject and replace it with the object,

-

Change the form of the main verb to its past-participial form,

-

Add some form of be to that main verb, and,

- Optionally indicate the original subject in a prepositional phrase headed with by

In the passive, the object preserves its grammatical role (being acted upon, or patient) but, in its sentence constituency, becomes the subject. Because the by phrase can be omitted without consequence, the passive voice can be used to obscure the original subject (or agent) or to avoid rephrasing it when it’s already understood in context. (Intransitive sentences have no objects to promote and so can’t be made passive.)

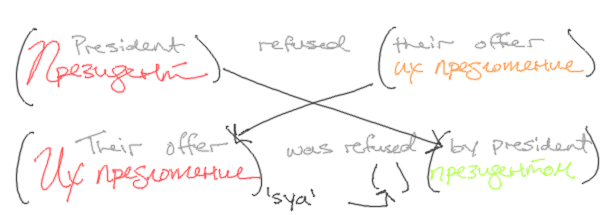

In Russian, it’s much the same:

- Move the object to the subject, removing the accusative indication

- Replace the main verb with its corresponding intransitive

- Optionally, indicate the original subject with the instrumental — not to "link", but to note means

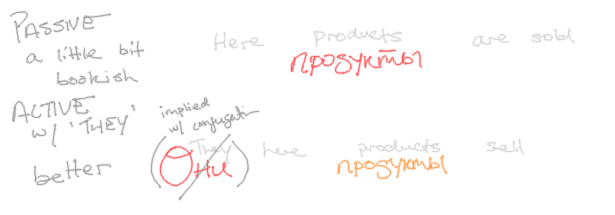

In conversational Russian, though, this too formal and less preferred to the active voice, using "they" when the agent is unimportant to the sentence:

Status

Verb status is a term used to describe three, distinct but difficult-to-disentangle qualities of a verb: tense, aspect and mood. Although different languages will have different cardinalities, each main verb has one of each:

-

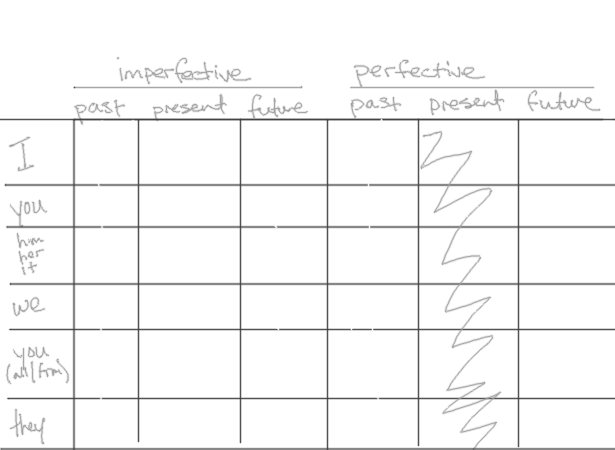

Tense indicates, relative to the instant of expression, the time the named action occurred.

-

Aspect is commonly referred to as the "fabric" of time and can indicate things like whether the action has been completed or is repeating or is continuous.

- Mood indicates the intent of the sentence, e.g. an assertion of fact, question of fact or an expression of doubt.

Tense and aspect are too different between the languages to pose side-by-side, so I’ll cover one at a time.

English Tense and Aspect

English verbs, with few exceptions, exist in at most five inflected forms (or principal forms):

- The base form is tenseless and used in infinitive phrases

- -s form is the present indicative and 3P singular

- Past (or preterite) forms the simple past

- Past participle form is used for the perfect aspect

- (Present) participle form ("-ing") is used for participle, gerund and deverbal nouns

With about 100 irregular exceptions, the past participle form is usually identical to the past form.

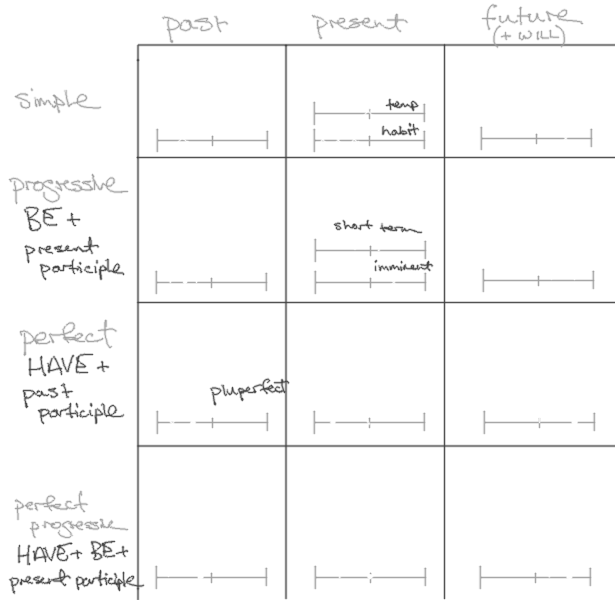

English recognizes three tenses centered around the instant of expression — past, present and future — over four aspects: the "simple", the progressive, the perfect and the perfect progressive:

There are many exceptions that make this chart worthy of its own discussion. I’ll say simply that the progressive aspect is used to indicate that an action is completed over some duration and the perfect aspect is used to indicate that an action has a finite end and to emphasize some result thereof. (The past perfect is similar in meaning to the Latin pluperfect.) They can be used alone or together. Without either, the simple aspect is used when the continuity or duration can be inferred from context.

To construct these phrases, we add modals (or modal auxiliaries or helping verbs) to the phrase and "port" the supplemented verb’s tense to it. Here are some rules for construction:

-

For the simple past tense, use the inflected past form.

-

For future tense forms, attach will / would (putting it in the conditional mood).

-

For progressive forms, attach some form of be and use the present-participle inflection.

-

For perfect forms, attach some form of have and use the past-participle inflection

- For progressive perfect forms, add both have and be and use the present-participle inflection.

Russian Tense and Aspect

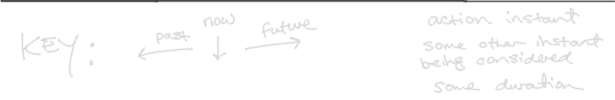

Russian, in contrast, recognizes twelve inflected forms for each verb and three tenses over two aspects:

Russian verbs occur in aspectual pairs: two words for each verb — one for the imperfective aspect and one for the perfective. The imperfective aspect indicates action that’s ongoing, repeated or in progress. The perfective aspect (distinct from English’s perfect) indicates action that’s either completed or is expected or intended to be completed in the future. The two always share a stem, but the perfective may have a prefix (e.g. гулять / погулять), an infix change (e.g. отвечать / ответить, начинать / начать) or completely different (e.g. сказать / говорить / поговорить, брать / взять).

Present-tense forms are conjugated over number and person (two numbers and three persons, with second plural "you all" exhibiting T-V distinction) and past-tense forms are conjugated over gender and number. The future imperfective uses the (unforgotten) perfective forms of быть, where the perfective lacks the present altogether (by that, inductively, the set of actions already completed and actions still ongoing are completely disjoint). Because Russian is less resolute in aspect, it translates ambiguously, e.g. “он читает” can be either “he reads / has been reading (regularly)” or “he’s reading (now)”.

Mood

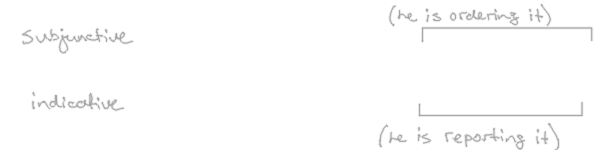

The indicative mood, in English and in Russian, can be considered "default": without indicators telling otherwise, expressions can be assumed to be describing the speaker’s understanding of reality.

The conditional mood expresses the speaker’s uncertainty and appears in English with modals like can/could, shall/should, will/would, may/might and must. (Remember from before that will forms the future, which is inherently uncertain.) Although the name seems to imply that it should occur in an if/then-type construct, it’s really the presence of these modals that governs the mood.

The subjunctive mood, another irrealis, is also concerned with the hypothetical. It indicates action that’s object to e.g. a desire, request or insistence. Altogether, it’s being lost in modern English and a bit formal for conversation. Its mechanics are both complicated and disputed enough that I’ll avoid anything but a cursory mention.

In Russian as well, this distinction is blurry but the syntax is simple: irrealis is accomplished with a heritage conjugation of быть over the defunct aorist aspect: бы (by).

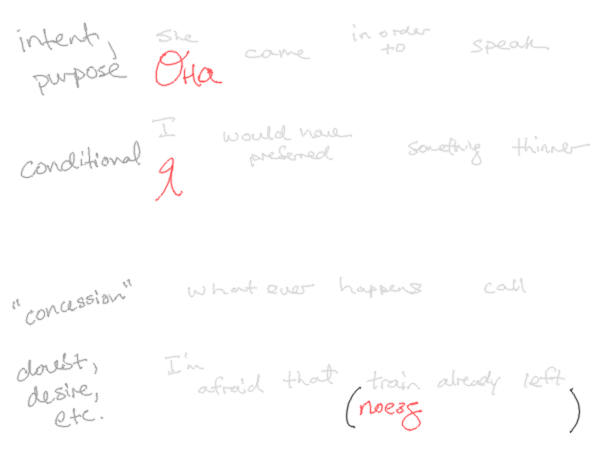

It’s used to indicate conditionals, several subordinate-clause constructions that pair well with the subjunctive in English, causal intent (i.e. "in order to/that", “so that”), personal inclination (as an alternative to the impersonal expression named in the reflexives section, e.g. я бы спить / мне спиться) and a strange construction that I’ve seen referred to as concessions that correspond to English -ever indefinite pronouns.

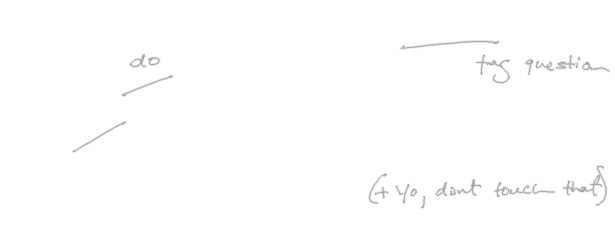

The imperative mood indicates command. In English, they’re usually recognized by a bare infinitive without a subject (e.g. "Stop!"), itself always implied “you”. Descendent from the tag question of the form “you will X, won’t you?”, the second-person imperative deletes you and will. Since the modal will carries the tense of the expression, we add do as an expletive when negating to anchor the not (i.e. “(you) do not” instead of “(you) not”). When the command is directed at us (cohortative mood) or him/her/it (jussive mood) instead of you, we use let and the bare infinitive (e.g. “Let’s go!” or “Let him be!”).

Russian has two inflected forms for imperatives with characteristic suffixes -ь(те)/-и(те)/-й(те), one for each number. Most generally, imperatives in the imperfective have a commanding tone (i.e. "be doing this now") while ones the perfective have a more polite one. The jussive is made with пусть (just as in English, from пускать / to let, e.g. пусть он вспомнит / let him remember) and the cohortative with the first-person plural in the perfective (e.g. “давай пойдем” / let’s go).

Verbals

Gerunds and Infinitives

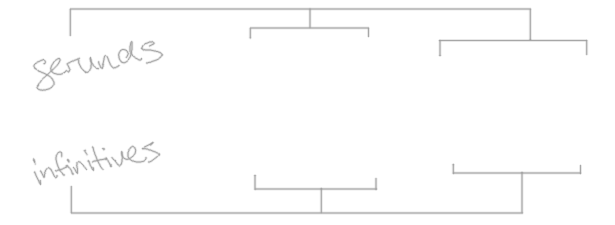

In English, gerunds and infinitives are two ways to produce a noun phrase from a verb. Gerunds occur in the participial -ing inflection and infinitives — like their name suggests — are formed from the infinitive. Although gerunds and infinitives should be technically interchangeable, infinitives often have a more literary character to them and sound unnatural in normal conversation and are difficult to choose between for nonnative speakers.

The Russian infinitive is also considered the verb’s uninflected, "dictionary" form and takes the characteristic endings -ть/ти-/ч. It behaves similarly to the English infinitive but is relied on for a few more roles (e.g. compound future будет, impersonal constructions) for lack of other analogous features — gerunds among them. The word is, I think, mistakenly used to refer to adverbial participles (or transgressives), which don’t produce nouns. I haven’t yet found an answer in English-language literature to whether verbal nouns (i.e. -ость, -ние) are result from a comparable process. The above example isn't colored because gerunds-as-nouns would take the form of infinitives in Russian and that verb form is never declined.

One interesting use, though, is a kind of impersonal and strong imperative (e.g. не курить / "no smoking"). Russian Language Mentor has a colorful explanation of this worth reading.

Participial Phrases

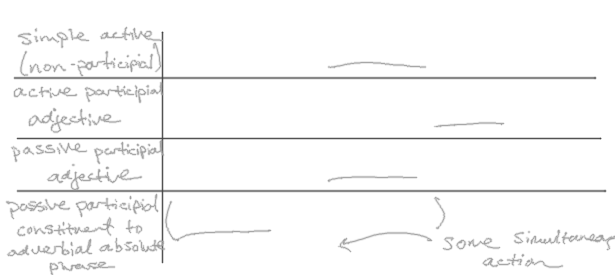

Participial phrases are verb phrases that behave either as adjectives or as adverbs. Used as an adjective, they can inline into a phrase what would otherwise be a relative clause (using "that", “who”, “which”, etc., e.g. “the affected parties” are “the parties that were affected”). Used as an adverb, they’re useful for composing compound predicates indicating simultaneous action by sharing two verbs to a common subject, usually in an absolute phrase, e.g. “Having finished work, she returned home”.

The topic of participles overlaps what I’ve previously mentioned about the progressive aspect and the passive voice. Even in this new part of speech, observations of recipiency remain the same: used in the past, participles indicate passiveness (i.e. "being object to") and, used in the present, they indicate activity (i.e. "being subject to").

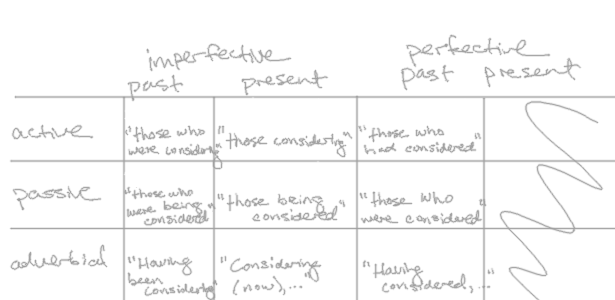

In Russian, there are six inflected participial forms for imperfective verbs and three for perfective ones: active, passive and adverbial forms over the past and present tense over two aspects — with the present-perfective ones absent. They are true adjectives, taking on the adjective’s -ий/-ый endings and being subject to its declension.

The main difficulty in grasping the Russian participial is its complex spelling rules. Morphology aside, this Russian verbal also behaves very similarly to its English counterpart. Russians instinctively reduce to it from который (catch-all which) phrases.

In the active, it’s common to see the modified noun omitted. Here again, the passive agent is indicated by the instrumental case. Participles can be formed from both transitive and intransitive verbs. (Predictably, passives for intransitives don’t exist.) The adverbial participle seems reserved exclusively for simultaneous action.

An interesting and still-unanswered question: are the transitive-passive and intransitive-active participles equivalent (e.g. интересующийся / интересуемый)?

Phrasal Verbs

English phrasal verbs are those that have been used with additional particles (which are disputed to be adverb or preposition) so often that they’re been incorporated into the verb itself, forming multi-word verbs with distinct meaning. They’re relatively new.

They would otherwise be unremarkable if their construction weren’t so complicated. Some are transitive (e.g. to give away, to look over, to throw away), some are not (e.g. to eat out, to grow up, to come back). Some transitives allow the object in-position (e.g. "leave the details out" and “leave out the details”) and some forbid it (e.g. “look into the case” but not “look the case into”). Some take on two particles (e.g. to get around to, to put up with). Some have multiple meanings (to make out: to kiss and pet or to interpret clearly, to hold up: to delay or to rob) and some share the same meaning (e.g to drop by, to drop in).

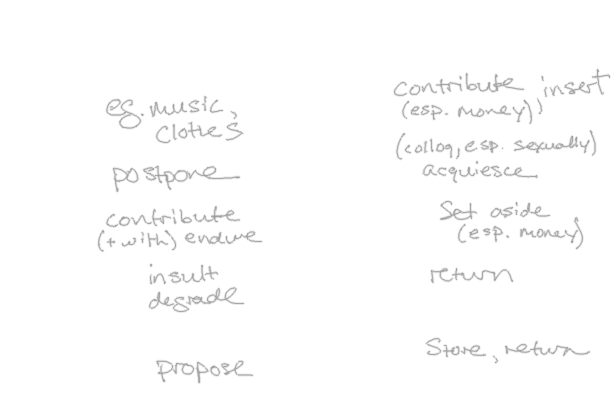

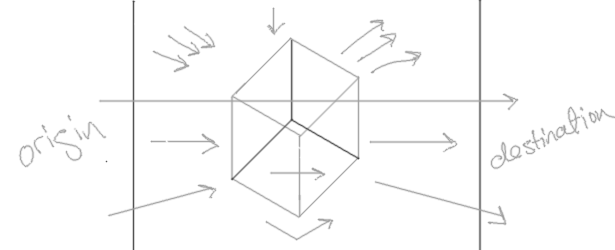

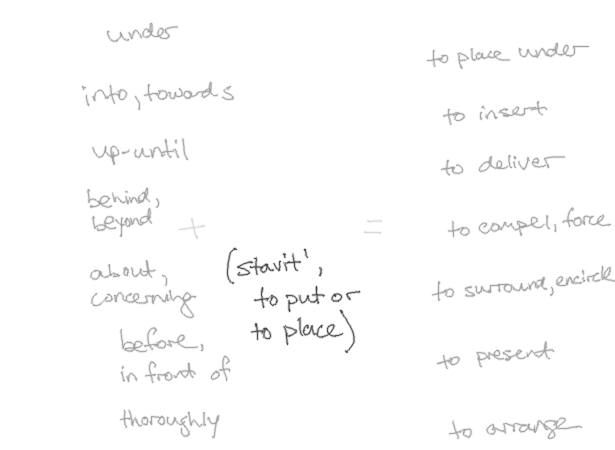

Foreign learners will bemoan that a small change in particle drastically changes these verbs’ meaning. Their origins are obscure and their semantics are delicate to context. Without question, the Russian verb prefix is functionally the same and is its most analogous feature. As we have "in", “by”, “out”, “into”, etc., the prefixes “в-”, “на-”, “у-”, “с-” — themselves also standalone prepositions — are affixed to verbs to augment the character of the base verb to produce more colorful ones. Although the mechanics are almost identical, the notions attached are completely different and so the two are notoriously difficult to translate.